Author: Anton Vatcharadze

On 27 August 2019, the historian Sergey Bondarenko published an article called “Stalin – Insole, Goat, Hooligan” (“Stalin – stel’ka, kozyol, khaliugan (sic)” in which he presented five different stories of insulting the Great Leader in the 1930s based on criminal case files. [1]

In this article, Bondarenko observed that due to centralized control and the absence of free elections, today it is impossible to establish whether Stalin was actually beloved by the citizens or not: “It is impossible to say anything about Stalin’s popularity in the 1930s. To find out real public attitudes in a country where there were no competitive elections, free media, of public surveys, the only potentially reliable source is memoirs, as well as the reports and minutes of NKVD about public attitudes. Criminal cases brought against the individuals with opposing and discontent views hold the most interesting information:

According to such sources, an omnipresent love toward the Leader is highly questionable. The protagonists of such documents are mainly ordinary people with a low level of education who do not belong to the higher circles, and they say extraordinary things about Stalin. Many detainees were sending the letters to him, asking for pardons and for help. Meanwhile, in the confessions many threatened to kill, mutilate, and rape the Leader… Such confessions were unquestionably written as the result of torture and humiliation. In such cases, the “criminal aspect” is simultaneously absurd and cannot be verified. Were such threats exaggerated? Could they have been invented by the confessor? Whether they were true or not, the fact is that the fixation on these ideas and attitudes, impulsive or deliberate actions, reflect the spectrum of attitudes toward Stalin and the “Soviet government” standing behind him. Even a fragmented collection of such opinions provides a unique chance to look into people’s subconscious during the epoch of this mass political terror. [2]

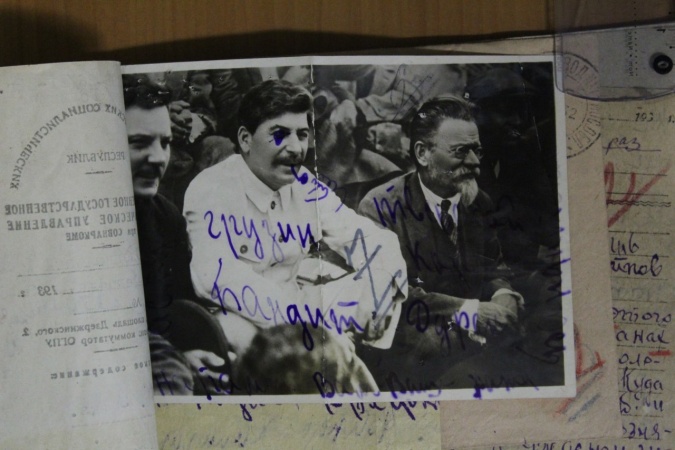

In Bondarenko’s article one particular detail stands out, on which the author himself does not focus. A case dated 8 April 1933 concerns a citizen named Malinin who was arrested for sending an insulting letter to the Kremlin, criticizing Stalin for causing starvation through the policy of collectivization. The file includes a photograph of Stalin on which Malinin has written the epithets of “Bandit”, “Fool” and “Georgian”.[3] Bondarenko did not go into detail about these epithets, but it seems from the documents that for the factory worker Malinin “Georgian” was an insulting word.

A photograph preserved in Malinini's case with an inscription - "Georgian" (Грузин)

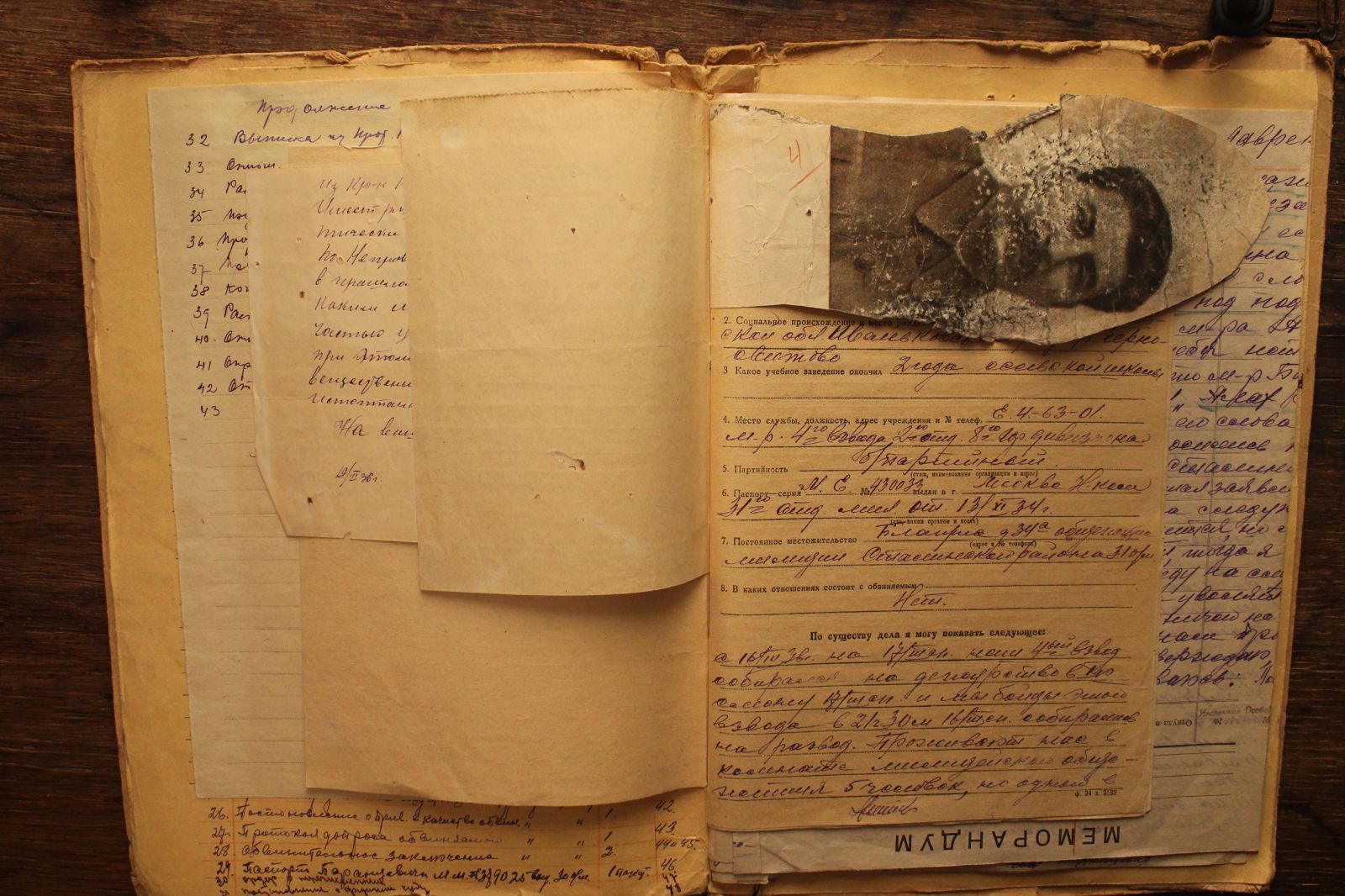

The document preserved in Russian historical archive

The stories and the investigative files explored by Bondarenko clearly show the face of the regime, which was led by the Georgian Joseph Stalin in the 1930s. Sergo Orjonikidze was also highly influential in the leadership, and Lavrenty Beria was in the Transcaucasus preparing to take on a position in the highest echelons. There is a worldwide consensus that the Stalinist regime was an unjust one: some people could be imprisoned for years on the basis of a conversation, while others were patronized and their behavior was explained by the lack of education (as in the case of one Savin in Bondareko’s article, who was found not guilty on the basis of his low level of education and political illiteracy).[4]

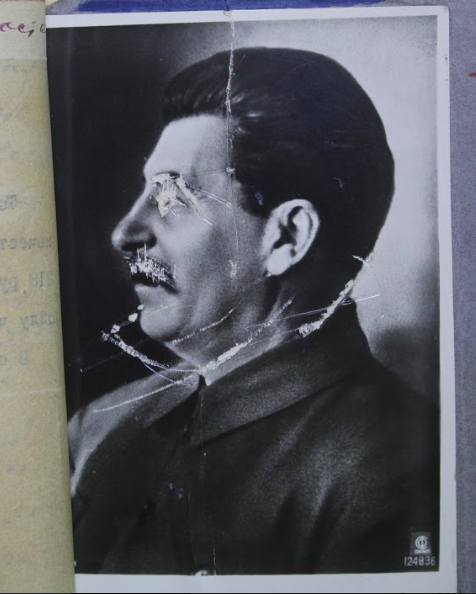

"Evidences": 1 - Photo of Stalin scratched with a nail

2- Shoe diaper cut from a portrait of Stalin

The document preserved in Russian historical archive

The Soviet Union subsumed heterogeneous nations on its vast territory, and from the very beginning the regime aspired to incorporate all of these peoples into one political nation. In the 1920s the policy of Korenizatsiia was implemented, which meant the purposeful development of local, non-Russian ethnicities. [5] After 1932-1933, the Party modified this policy and would later carry out repressions against its active supporters. Korenizatsiia changed into a policy emphasizing Russification based on the principle of “Friendship of the Peoples,” which also affected the educational sphere. This meant that the Soviet regime supported the development of ethno-nationalist sentiments among the titular nations in the Union republics [6], while at the same time considering Russian nationalism and culture as the first among equals. [7]

Thus simultaneously Russia was considered superior, but the Leader was from the peripheral Caucasus, while his fellow-countrymen and the other Caucasians were being actively promoted. As Lavrenty Beria’s son Sergo recalled in his memoirs, it was his father who first provided Stalin with the idea of holding Dekadi (ten-day celebrations) of the cultures of each Soviet republic in Moscow to show the positive influence of Soviet Russia on their cultures According to Sergo Beria, Stalin liked this idea and represented it as his own. [8] It is impossible to prove whether this was truly Beria’s initiative solely based on these memoirs, but it is a fact that from 1936 such Dekadi were regularly held in Moscow. In 1937 a Georgian Dekada was held after those for the Ukrainians and the Kazakhs. Among the cultural activities included were not only traditional aspects and folklore, but also performances of “high” culture such as ballet and opera. [9]

The 1937 Dekada helped shape the general attitude in the Soviet Union toward the Georgians and Georgia: first of all, in included the epithet of “Sunny Georgia” (“Solnechnaia Gruziia) which is still associated with it in Russian-speaking countries. According to the newspaper Pravda and other reviews in the press, it was the warm weather and sun that determined the joyful nature of the culture of the Georgian people. During the Dekada phrases such as “Great nation and culture” and “thousand-year-old history” were used abundantly. [10] However, even Russian authors of that time observed that the Russian elites patronizingly considered the national cultures of the republics to be something exotic. [11]

The 1937 Dekada helped shape the general attitude in the Soviet Union toward the Georgians and Georgia: first of all, in included the epithet of “Sunny Georgia” (“Solnechnaia Gruziia) which is still associated with it in Russian-speaking countries. According to the newspaper Pravda and other reviews in the press, it was the warm weather and sun that determined the joyful nature of the culture of the Georgian people. During the Dekada phrases such as “Great nation and culture” and “thousand-year-old history” were used abundantly. [10] However, even Russian authors of that time observed that the Russian elites patronizingly considered the national cultures of the republics to be something exotic. [11]

The ordinary Soviet stories, seemingly harmless at the first sight, also speak to the “sunny” image of the Georgians formed in the 1930s: for instance, Kansas University professor Eric R. Scott, in his article “Soccer Artistry and the Secret Police: Georgian Football in the Multiethnic Soviet Empire,” describes a meeting of the USSR Football Federation in 1970 at which its head, Valentin Granatkin, irritated by the boasting of the Georgian delegate Tsomaia, interrupted by exclaiming “Only because you have no winter!” [12] Scott also authored the book Familiar Strangers: The Georgian Diaspora and the Evolution of Soviet Empire, in which he describes the influence of the Georgian feasting tradition (the supra) on the whole Soviet Union, making the toast a part of the traditional culture of Central Asia and elsewhere.

After Stalin’s death and Beria’s execution in 1953, the attitude of the center toward “sunny” Georgia and its sons began to change. The accumulating covert jealousy openly erupted in February 1956 at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when during his “Secret Speech” Khrushchev not only emphasized the crimes committed by Stalin personally, but also linked them to his ethnic origins. [13]

Rumors about the contents of Khrushchev’s “Secret Speech” quickly began to spread in Tbilisi, resulting in the well-known events of March 1956: public protests were held to defend the name of Stalin, during which there was a noticeable intensification of nationalist sentiments and sloganeering. The demonstrations were ultimately crushed violently by the Soviet security forces. It is noteworthy that calls for national independence and the first underground nationalist dissident movements began in Georgia right after the 1956 events. [14]

The “Secret Speech at the 20th Party Congress and the rehabilitation of the victims of 1937-1938 mass terror in 1955-1956 can be considered an attempt of the Politburo members, including Khrushchev, Malenkov, and Mikoyan, to avoid personal responsibility for their own roles in deciding the fates of thousands of people during the Stalinist Terror. They presumed that blaming Stalin and Beria for everything would absolve them from their responsibility before history.

Georgians’ anger at Khrushchev’s destalinization can also be explained by the argument that either consciously or unconsciously Georgians perceived the attack on Stalin as an attack on Georgia. Khrushchev’s attempt to diminish the role of Georgia in the hierarchy of the Soviet republics was evident, although whether the Georgia had a privileged status under Stalin and Beria is contentious topic even today among historians (especially Georgian ones, many of whom disagree). It should also be noted here that Khrushchev had his own clients in Georgia, such as the new First Secretary of the Communist Party in Georgia, Vasil Mzhavanadze, and the Georgian KGB head Aleksi Inauri. Nevertheless, Khrushchev understood well that Georgians would never forgive him for the attack on Stalin and Georgia. [15]

Following the 1956 events and the demonstration of raw power by the regime, the attitudes toward Georgians gradually settled. According to various oral histories, Khrushchev several times threatened Georgians with strict measures and deportations [16], although there is no documentary evidence for this. Through First Secretary Mzhavanadze’s diplomacy and Khrushchev’s liberal policy, Georgians attained a new role in the Soviet commonwealth, one that was mainly limited to the realms of hospitality, cuisine, singing, dancing and performing elaborate toasts (by the tamada, or toastmaster). Yet there remained the demands of Empire. The ephemeral “love and respect” towards Georgia and its culture was (and still is) in place only until such time as it interfered with the “comfort zone” of the Russian Empire, and the Georgians aspired to break out of their designated role.

In differing forms, the Georgians attempted to go beyond this defined role in 1956, in 1978 and in 1989. All of these cases came at great cost in terms of lives and public order. More recently, this has mass deportation of Georgians from Russia in cargo planes, the August war in 2008, the so-called “Gavrilov Night” crisis [17] in 2019 – all of these can be considered as punitive measures against the attempts of Georgians to transcend the role that Russians have defined for them.

Deportation of Georgians from Russia with cargo plane, 2006

Photo: netgazeti.ge

Of course, a single phrase written on a photograph is a limited basis on which to construct a hypothesis about how attitudes toward the Georgians in the Soviet Union may have deviated from the official stance. However, it can be argued that the word “Georgian” written on Stalin’s photo, together with the other offensive words of the factory worker Malinin, expresses a kind of authenticity. This one expression says more than a great many of the official sources that were subject to censorship. Given the lack of documents, it would be impossible today to prove, but it is certain that in in the Kremlin and among the Soviet public the voices of Malinin and others were understood clearly, and were payed attention to. Based on this, it can be argued that the Georgian cultural days in Moscow in 1937 were organized by the two Georgian leaders of the Party and the Soviet state in order to improve to some extent the negative image of Georgians. It can also be hypothesized that for the many Russians who suffered through the repressions, World War and the totalitarian regime, Stalin’s home country of Georgia did not hold singularly “sunny” associations.

___

[1] Goat (kozyol) is an offensive epithet in Russian.

[2] https://urokiistorii.ru/article/56072 (accessed March 10, 2020)

[3] GARF, f.10035, d. P-1551.

[4] Based on GARF, f. 10035, d. P-1041.

[5] George Liber, ‘Korenizatsiia: Restructuring Soviet Nationality Policy in the 1920s’, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 14, 1991, 1, pp. 15-23.

[6] Titular nations were the dominant ethnic groups in the particular Soviet republics: Georgians in Georgia, Armenians in Armenia, etc.

[7] Terry Martin, The Affirmative Action Empire: Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923-1939, Cornell University Press, 2001.

[8] Sergo Beria, Moi otets Beriia. Vkoridorakhstaliskoivlasti, Moscow, 2001, p. 46.

[9] The Georgian ballet created specifically for the 1937 dekada was an example of Socialist Realism: in the first act, collective farmers work happily in the fields; in the second act, evil imperialists come and attempt to subvert this happy life; in the third act, the brave Bolsheviks arrest and punish these imperialists and life returns to its usual rhythm.

[10] Martin, The Affirmative Action Empire, p. 443.

[11] E. Gal’perina, “Formy proiavleyiia velikoderzhavnogo shovinizma v literaturovedenii i kritike,” PAPP, nos. 5-6 (1931), p. 47.

[12] Erik R. Scott, “Soccer Artistry and the Secret Police: Georgian Football in the Multiethnic Soviet Empire,” in The Whole World Was Watching: Sport in the Cold War, Robert Edelman and Christopher Young, eds., Stanford University Press, 2020.

Georgian translation: https://www.idfi.ge/archive/index.php?cat=read_topic&topic=151&lang=ka (accessed March 10, 2020).

[13] Claire P. Kaiser, “A silent kind of protest”? Deciphering Georgia’s 1956 (First published in: Georgia After Stalin: Nationalism and Soviet Power, Timothy K. Blauvelt and Jeremy Smith, eds. (BASEES/Routledge Series on Russian and East European Studies, 2015).

[14] Giorgi Kldiashvili, “Nationalism after the March 1956 events and the origins of the national-independence movement in Georgia,” Blauvelt and Smith, eds., Georgia After Stalin.

[15] Timothy Blauvelt, “Status Shift and Ethnic Mobilisation in the March 1956 Events in Georgia,” Europe-Asia Studies, v. 61, n. 4 (2009).

[16] Memoirs of Vasil Mzhavanadze's daughter Nina (various sources on the Internet).

[17] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-48710042 (accessed November 23, 2020)

Publication of this article was financed by the Open Society Institute Budapest Foundation (OSI) within the frame of the project - Enhancing Openness of State Archives in Former Soviet Republics and Eastern Bloc Countries. The opinions expressed in this document belong to the Institute for Development of Freedom of Information (IDFI) and do not reflect the positions of Open Society Institute Budapest Foundation (OSI). Therefore, OSI is not responsible for the content.