The existence of strict guarantees for the protection of privacy is essential for the establishment of a free and democratic society. The constitutional right to privacy is an integral part of the concept of freedom. It envisages the right of a person to form and develop relations with others, determine his/her place in a democratic society, form opinions and develop connections with the outside world. [1]

The existence of strict guarantees for the protection of privacy is essential for the establishment of a free and democratic society. The constitutional right to privacy is an integral part of the concept of freedom. It envisages the right of a person to form and develop relations with others, determine his/her place in a democratic society, form opinions and develop connections with the outside world. [1]

The right to privacy is not absolute. It can be restricted by law if it is necessary in a democratic society for ensuring national security and public safety or protecting the rights of others. The restrictions can only be imposed based on a court decision or without a court decision in the case of urgent necessity provided for by law (without a court decision). [2]

According to the European Convention on Human Rights, there shall be no interference by a public authority with the exercise of this right except such as is in accordance with the law and is necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security, public safety or the economic well-being of the country, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.[3]

Interference in the right of private communication conducted via phone or any other technical means constitutes the restriction of privacy. However, covert surveillance does not per se contradict the values of modern, democratic society. The interest of state security can on certain occasions require restricting civil liberties. In these cases, it is essential to have procedural safeguards and relevant control mechanisms necessary for preventing the abuse of power by the state.

The given study reviews the legal framework of covert investigative and intelligence activities, discusses existing gaps, international standards and assessments, and presents the trends identified based on the statistical analysis.

- Ensuring genuine independence of LEPL Operative-Technical Agency constitutes a significant challenge. Existing legislation still fails to set strict guarantees for the protection of privacy.

- The provision of the Law of Georgia on Counter-Intelligence Activities, according to which special services authorized to undertake intelligence activities are entitled to interfere in the private lives of individuals without court authorization, remains to be problematic.

- Based on the existing legislation, the Parliamentary Trust Group which exercises oversight in the area of state defense and security does not possess relevant mechanisms of control and supervision. The existing rules of overseeing the activities of Operative-Technical Agency are vague and do not allow for detailed oversight of its activities.

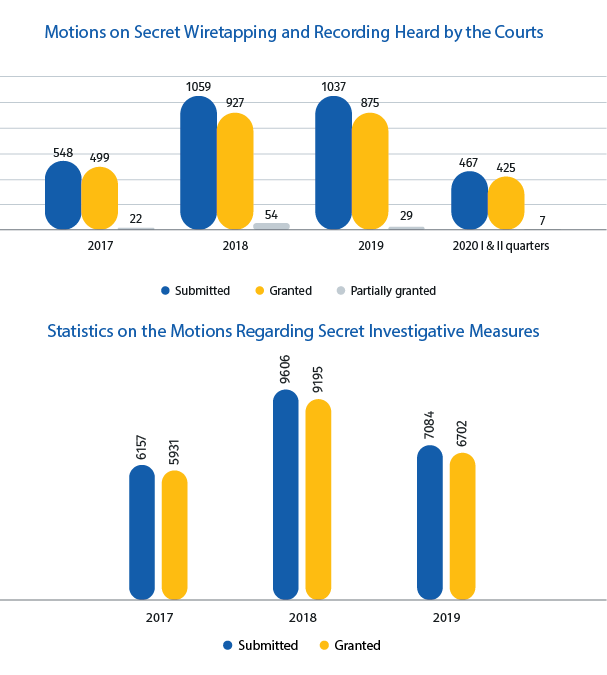

- According to the data, the total number of motions on wiretapping received by courts from 2016 until the end of the second quarter of 2020 equaled to 3 467. The trend of a rising number of motions has been observed in Tbilisi since 2016. In 2019 the number further increased by 1.6% compared to the previous year and reached the highest figure of 669.

- During 2019 a total of 7 084 motions on covert investigative measures were submitted at city and district courts of Georgia.

- The number of motions on covert investigative measures decreased by 26.3% in 2019 compared to the previous year. Based on the data of 2019 the percentage of granted motions slightly decreased as well. In 2018 the ratio of granted motions equaled to 95.7%, while in 2019 the figure fell to 94.6%.

- Based on the data of 2019 49% of all motions on covert investigative measures recorded in Georgia were submitted at Tbilisi City Court, which indicates that the majority of such motions are accumulated in Tbilisi compared to other city and district courts.

- During the last four years, the ratio of granted motions on wiretapping has been gradually decreasing: in 2017 the figure equaled to 91%, in 2018 – to 88% and in 2019 to 84%. Since 2017 the highest ratio of granted motions was recorded in the first two quarters of 2020 – 91%. However, the ratio of granted appeals can change multiple times until the end of the year.

- Compared to 2018 the number of motions on wiretapping reviewed by the courts decreased in 2019, however, the figure doubled compared to 2017.

- It is noteworthy that during 2019 the number of motions on wiretapping linked with fraud increased by 50% compared to the previous year. In 2019, the number of motions linked with murder or intentional infliction of grave injury also increased. At the same time, the number of motions on wiretapping linked with robbery decreased by 61.4%, while the motions linked with the membership of the criminal underworld (thief in law) decreased by 36%.

- During the period from 2016 until the end of the second quarter of 2020 66.2% of all motions on wiretapping were recorded in Tbilisi, while the remaining 33.8% were spread across 23 city/district courts. The figures demonstrate that the majority of motions on wiretapping are accumulated at Tbilisi City Court.

Conclusion

Respecting personal autonomy and minimizing interference in the private and family lives of individuals is vital for establishing a free, democratic society. The main purpose of the right to privacy is to protect individuals from arbitrary interference by the state on their personal and family lives.[4]

The state has a positive obligation to protect the human rights of those under its jurisdiction. Consequently, crime prevention and the protection of state security are integral parts of state functions. However, in performing these functions the risk of arbitrary interference in personal freedoms and abuse of power is particularly high. The wider the mandate, higher the level of its ambiguity and lower the oversight over the body, the higher the risk. To prevent arbitrary interference in personal freedoms and circumvent abuse of power the conduct of secret investigative measures should be subjected to unbiased oversight and control.

As for the practice of secret investigative measures, statistical analysis indicates that the trend of the rising number of motions submitted at the courts changed in 2019 and the number of motions decreased compared to the previous year. However, the figures of 2019 are still considerably higher than the numbers reported in 2017. As for the motions on secret wiretapping and recording, during the last four years, the ratio of granted motions have been slowly and gradually decreasing. A different picture is demonstrated by the data from the first 6 months of 2020, when the ratio of accepted motions was considerably high (91%). However, the picture can significantly change until the end of the year.

Under the current regulations, there is little trust that in the conduct of secret investigative measures state interference in private life would be proportional to its legitimate aim. Lack of trust towards the government is dwelling from its reluctance to address the challenges, which are being highlighted by various international as well as domestic organizations.

___

[1] Ketevan Eremadze, Freedom Guardians in Search of the Freedom, pg.163.

[2] Constitution of Georgia, Article 15, para. 2.

[3] European Convention of Human Rights, Article 8

[4] Ruling of the Constitutional Court of Georgia, February 29th 2012, case N2/1/484, Georgian Young Lawyers Association and the Citizen of Georgia Tamar Khidasheli v. The Parliament of Georgia, II, 15.

/public/upload/Rule_of_Law/secret_surveillance_in_georgia-ENG.pdf

/public/upload/Rule_of_Law/secret_surveillance_in_georgia-one-pager-eng.pdf

This material has been financed by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, Sida. Responsibility for the content rests entirely with the creator. Sida does not necessarily share the expressed views and interpretations.