By: Eric Jackson, an intern within the framework of Overseas Professional and Intercultural Training Program, American Councils

Estonia is a post-Soviet Baltic nation of 1.3 million people, with Russia located on its Eastern border. The past ten years have seen Estonia implement comprehensive e-Government policies providing quality internet access to 70% of rural citizens (Statistics Estonia, 2012). In 2012, Estonia was the highest ranked post-Soviet country in e-Government capabilities by the UN Public Administration Program at 20th overall. Online e-Government services have integrated all aspects of Estonian society: doctors can view online medical records instantly; citizens can vote in national elections online, entrepreneurs can legally register a business in twenty minutes, and with 90% of Estonians having e-Identification cards, government services reach the majority of citizens. These examples show that a small post-Soviet nation can present e-Government services to rural citizens outside Tallin, the capital city where nearly a third of the population resides. The Transcaucasian Republic of Georgia is going through a similar online post-Soviet transition. Georgia’s population of 4.48 million spreads out over mountainous terrain, with nearly a quarter of the population living in Tbilisi, the capital. Georgia’s 2012 UN Public Administration Program rank of 72nd, respectively, achieved a 28 spot improvement from 2011’s rankings. Georgia’s e-Government policies have developed tremendously since 2010 by centralizing e-Government services through the Ministry of Justice’s LEPL Data Exchange Agency. Other improved e-Government services include the Civil Service Bureau’s 2013 United Nation’s Public Service Award (UNPSA) winning asset declaration page for government officials, decreasing public information requests four times since 2009. The Bureau also implemented an online job platform that helps job applicants find civil service jobs easier than before. In 2012, Georgia’s e-Government procurement system won the UNPSA for preventing and combating corruption in public service, along with the Ministry of Justice’s Public Service Hall for improving the delivery of public services. From an e-Participation standpoint, the Ministry of Finance created an online survey where citizens can prioritize budget allocation through a ranking system. While all of these online improvements are commendable, it is important that all Georgian citizens have better access to these enhanced government services. Thus, Georgia should take note on how Estonia monetarily prioritizes rural internet accessibility as key for economic development and inclusive rural e-Participation.

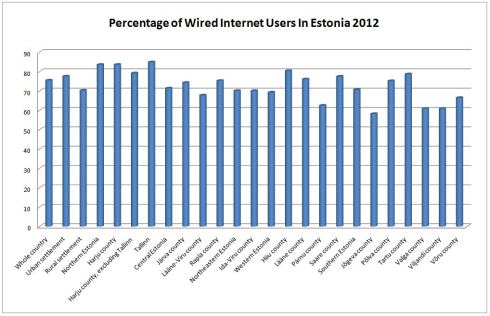

Both nations are dealing with the challenges of breaking free from Soviet mentalities and establishing online platforms from scratch, as opposed to the United States and the UK who had established IT infrastructure before the millennium. The Estonians understand better than any other post-Soviet nation that inclusive e-Participation by rural citizens can only expand e-Commerce, e-Democracy and government program access to citizens who would not have the means otherwise. By 2015, the Estonian government plans on connecting every household to the internet. The project, named EstWin, is due more than 6,000 km of fiber-optic cables through 1,400 connection points. The cost of the project is €95.8 million, with the Estonian government paying three quarters and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) paying the last quarter of the bill. The Estonians may not be financially perfect, but they have set a budgetary precedent allocating the necessary funds to expand internet access. It is worth noting the ITC culture and infrastructure of Estonia is already well developed. In 2012, 78 percent of the Estonian population used the internet (ITU, 2012). In comparison, the percent population of Georgian internet users was 37.8 percent (ITU, 2012), a number that does reflect improvement in broadband subscribers since 2011. Tbilisi alone has 251,788 registered wired internet users, accounting for 64% of all wire connected internet users in Georgia. With over 2 million Georgian citizens identified as rural residents (GeoStat, 2013); the need for internet accessibility for the rural population outside of Tbilisi is important for economic and democratic development, a principle Estonia has fully recognized.

As the Caucasus Research Resource Center’s recent survey indicated, the majority of the Georgian population does not have internet access for a variety of reasons. Clearly, this limits the amount of e-Participation that can occur for Georgians, especially in rural areas where there is no form of internet access. For instance, in the region of Mtskheta-Mtianeti, there are only 1,702 wired internet users out of an official estimated population of 109,700. The region of Guria represents similar disparity, with 2,075 wired internet users out of a population of 140,000. Even in other metropolitan areas, like Rustavi, a city of 122,000 in southeastern Georgia, there are only 23,446 wired internet users. The topography of Estonia makes establishing rural internet connection easier than in Georgia, but, if there is increased monetary investment in Georgian rural internet accessibility, e-Participation by rural residents will likely increase. At very least, rural residents will have the opportunity to be included in e-Government services through the continued funding of Village Development Centres proposed in Georgia’s Open Government Partnership Action Plan. As noted in IDFI’s Development of E-Communication in Georgia – Access to the Internet research, 27.9% of rural residents polled by the Caucasus Research Resource Center stated that not having access to a computer was the main reason they do not use the internet. Here lies an opportunity to develop multiple, free of charge, internet capable computer hubs rural citizens can access for e-Government services. These centers provide an enormous government service for rural citizens applying for passports, identification, land permits, bill payments, tax revenue collection, etc. Providing internet hubs for rural citizens will not only eliminate bureaucratic red tape for vital documents needed, but will improve e-Participation inclusiveness for Georgian society on a comprehensive level. That is why it is vital for the Ministry of Justice to continue allocating budgetary funds for rural Village Development Centres in the future.

As a short term goal, the Georgian government should make efforts to increase wired internet user access in other metropolitan areas outside of Tbilisi, such as Rustavi. In the long term, there has to be a budgetary priority improving internet accessibility for rural Georgian citizens to achieve e-Participatory expansion. The innovative Georgian idea of Village Development Centres should be allocated budgetary resources for sustained growth. Along with the Centres, developing rural internet infrastructure through connection points and fiber optic cables should be considered in next year’s budgetary process. As the Estonian government has recognized, working together with the private sector can limit the burden of solving technical issues providing internet access to rural localities. Once there is a budgetary commitment to the improvement of rural internet accessibility, Georgia will see economic and political participation benefits for the country as a whole and not confined to just Tbilisi.