Author: Fagan Abbasov, Researcher, Master at Georgian Institute of Public Affairs

Equal and full participation in civil and political processes is one of the priorities of democratic governance. Political integration of ethnic minorities living in Georgia remains a challenge to this day. The lesser extent of their participation in the decision-making process at the central and local levels contributes to a feeling of exclusion.

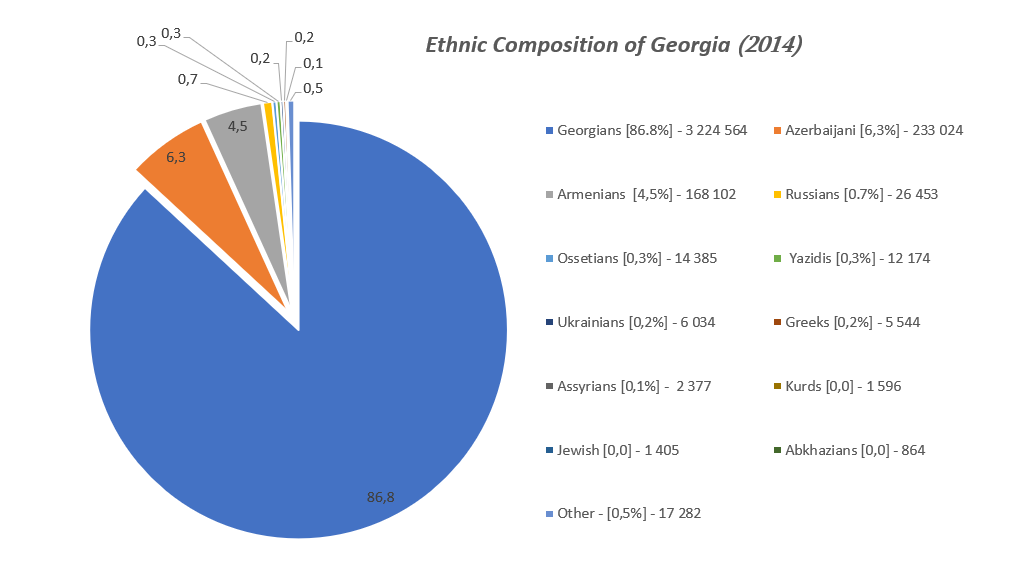

According to the last general census conducted in Georgia in 2014, ethnic minorities (excluding occupied Abkhazia and Tskhinvali regions) constitute 13.2% of the population (489,240 people). Two larger groups stand out in particular: the Azerbaijani community with 6.3% (233,024 people) and the Armenian community with 4.5% (168,102 people) [1].

(Source: National Statistics Office of Georgia)

There are no specific articles regulating the rights of ethnic minorities in the Georgian legislation. Article 11 of the Constitution prohibits discrimination and recognizes the equality of all people before the law [2]. Additionally, the Law of Georgia On Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination prohibits all kinds of discrimination, including discrimination on ethnic and religious grounds [3]. According to Article 23 of the Constitution, citizens of Georgia have the right to form a political party or another kind of political union and participate in its activities. However, there is a prohibition on forming a political party on a regional basis [2].

Through various international pacts and conventions, Georgia has taken on a responsibility to take specific steps and make legislative changes aimed at protecting the rights of ethnic minorities living in the country. Among them, one of the most important is the Convention on the Protection of National Minorities, signed by Georgia in 1995. According to paragraph 4 of the fourth article of the second part of the Convention, "The Parties undertake to adopt, where necessary, adequate measures in order to promote, in all areas of economic, social, political and cultural life, full and effective equality between persons belonging to a national minority and those belonging to the majority."[4]

Georgia began the implementation of a state strategy in 2009, one of the goals of which was/is to promote the civil and political integration of ethnic minorities. The 2009-2014 National Concept of Tolerance and Civil Integration[5] and the 2015-2020 State Strategy for Civil Equality and Integration[6] covered 5-year periods, and the new strategy approved in 2021[7] will be in force until 2030. According to the final assessments, the strategy developed by the state has a unified approach to both large and small and vulnerable ethnic minorities, although observations show that the steps taken in terms of political inclusion are focused on larger groups—the Azerbaijani and Armenian communities—and for the most part, do not cover the small ethnic groups.

Within the framework of the 2009-2014 National Concept of Tolerance and Civil Integration, the steps taken to strengthen the civil and political participation of ethnic minorities included the promotion of the European Framework Convention on the Protection of National Minorities, the translation of materials published by the Election Administration into Azerbaijani, Armenian, and Russian languages, and the organization of meetings with young voters and community representatives. According to the assessment of the mentioned strategy, the document acknowledged that the activities implemented to ensure full civil and political involvement were ineffective.[5]

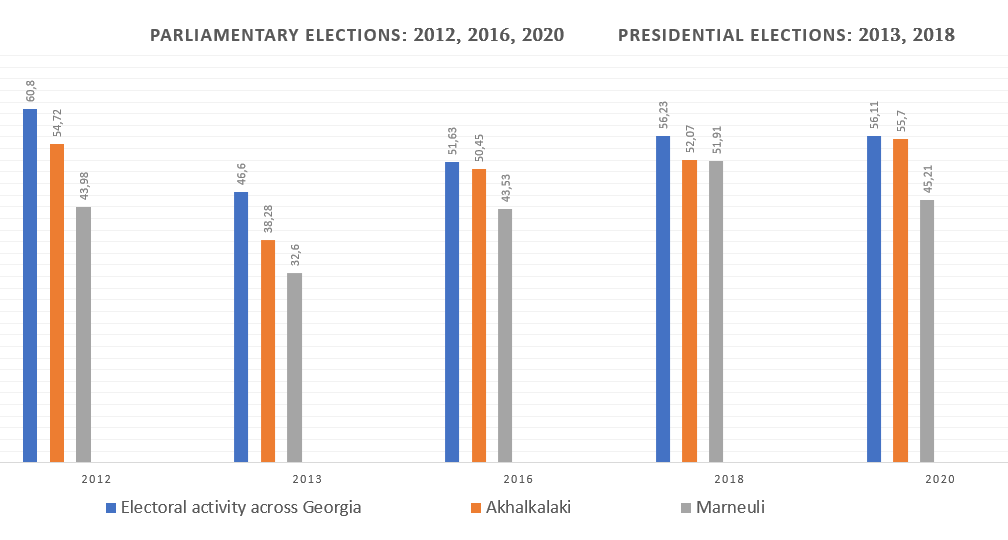

The 2015-2020 State Strategy also did not respond to the existing challenges in the direction of civil and political integration of ethnic minorities. According to the action plan, ensuring the ability to vote and make informed choices for representatives of ethnic minorities was one of the significant tasks. The activities of the Election Administration aimed at achieving this goal were largely similar to the previous strategy and were limited to the training of the members of the precinct election commission representing ethnic minorities, the translation of election materials and videos into their languages, and the organization of meetings/trainings with different groups of society. It should be noted that in the regions densely populated by ethnic minorities, no progress in the direction of voter activity has been observed at all. Voter turnout is traditionally lowest in the municipalities of the Kvemo Kartli and Kakheti regions, where ethnic minorities are densely settled. In this regard, the situation is relatively good in the municipalities of Samtskhe-Javakheti, although voter turnout there is, in many cases, still below the national indicator.

(Source: Election Administration of Georgia)

One of the objectives of the 2015-2020 State Strategy was to encourage the involvement of representatives of ethnic minorities in the activities of political parties and party lists. According to the final report, however, no effective steps were taken in this direction. Another objective in this direction, aimed at improving the legal framework and developing an appropriate model according to international standards to facilitate the involvement of ethnic minorities, also remained unfulfilled.

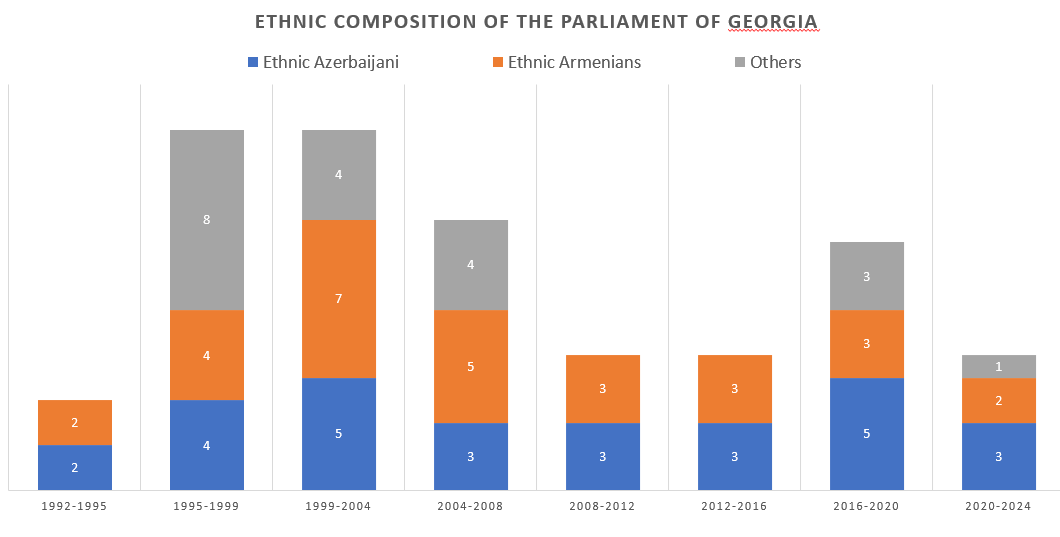

The representation of ethnic minorities in the Parliament of Georgia has remained a problem since the 90s. They had 4 representatives in the legislature in 1992-1995, 16 in 1995-1999 and 1999-2004, 12 in 2004-2008, 6 in 2008-2012 and 2012-2016, 11 in 2016-2020, and 7 in 2020-2024. The majority of MPs representing ethnic minorities belong to the Azerbaijani or Armenian communities.[6]

(Source: Centre for the Studies of Ethnicity and Multiculturalism)

Statistics show that the representation of ethnic minorities in the legislature has never been proportional to their share of the country's population. Ethnic minorities had 6 representatives in the Parliament of the tenth convocation, which means that they were at least three times less represented in the legislative body. It should be noted that in relation to the political involvement of ethnic minorities, in the absence of specific mechanisms, there has been no progress at all in terms of increasing their representation in the legislative body.

(Source: Centre for the Studies of Ethnicity and Multiculturalism)

In the case of a mixed electoral system, the representatives of ethnic minorities in the legislative body were mainly elected from majoritarian constituencies. In the case of a fully proportional system, taking into account the political involvement of ethnic minorities, there is a danger that their representation in the legislative body will be minimal. This, however, will depend on the electoral lists of the main parties.

In addition to the quantitative indicator, it is important to understand the involvement of ethnic minorities in the actual decision-making process, an important consideration. Political parties often prefer candidates who are quite passive. They fall in the category of "silent representatives" of the legislative body and never come forward with legislative initiatives. Among them are MPs of the 10th Convocation of the Parliament from the governing team, Samvel Manukian, and Sumbat Kiureghian, and Abdullah Ismailov from the opposition [8].

It should also be noted that there is no quota system or financial incentives for political parties in the Georgian legislation to facilitate the involvement of ethnic minorities in political processes. Consequently, the political involvement of ethnic minorities depends on the "goodwill" of political parties.

Various studies have demonstrated that the ties between ethnic minorities and political parties are rather weak, and as a consequence, trust in political parties is low. Only 12.6% of respondents from ethnic minorities state that they trust political parties ("mostly trust" or "completely trust"). Only 16.1% of them agree with the statement that the activities of political parties incorporate the needs and issues that are specifically related to their ethnic group. 46.4% of the respondents disagree with the above statement, and 37.4% have no answer to the question. [9]

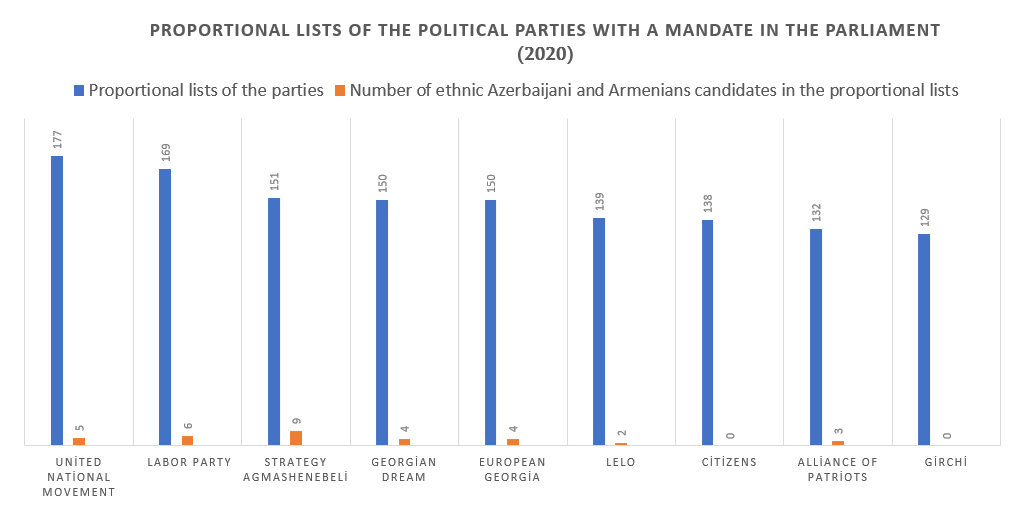

As a result of the 2020 parliamentary elections, 9 political parties won mandates in the legislative body. The analysis of their proportional lists shows that the representation of ethnic Azerbaijanis and Armenians is very weak. Only 33 of the 1,335 candidates on the proportional list of the 9 political parties with mandates in the 10th convocation parliament were ethnically Azerbaijani or Armenian [as identified by first and last names].

(The diagram was prepared based on the proportional lists of political parties)

(The diagram was prepared based on the proportional lists of political parties)

It should also be noted that the representatives of ethnic minorities in the proportional lists of the parties in many cases fell into positions that had only a theoretical possibility of getting into the legislative body. None of the above-mentioned political parties have a representative of an ethnic minority in the top ten of the 2020 proportional list. "Alliance of Patriots of Georgia" had the representative of the ethnic minority in the 14th spot in the proportional list, "United National Movement" – 17th, "Labor Party" – 18th, "Strategy Agmashenebeli" – 25th, "Lelo" – 26th, "European Georgia" – 28th, and "Georgian Dream" – 35th[10]. Additionally, the analysis of the electoral platforms of political parties shows that in most, the issues related to ethnic minorities were either not reflected or presented only in a formal manner.

The representation of ethnic minorities in the political councils of parties is quite small, which reduces their involvement in internal party decisions accordingly. Of the 9 parties that crossed the threshold as a result of the 2020 parliamentary elections, for example, the number of ethnic minorities in the 129-member political council of "United National Movement" is three, and in the 32-member political council of "European Georgia" - two. There are no representatives of ethnic minorities in the political councils of the remaining barrier-crossing parties.

In addition to the legislature, there are virtually no representatives of ethnic minorities at the executive level. No minister or deputy minister is a representative of an ethnic minority. At best, they occupy low-level positions at various agencies.

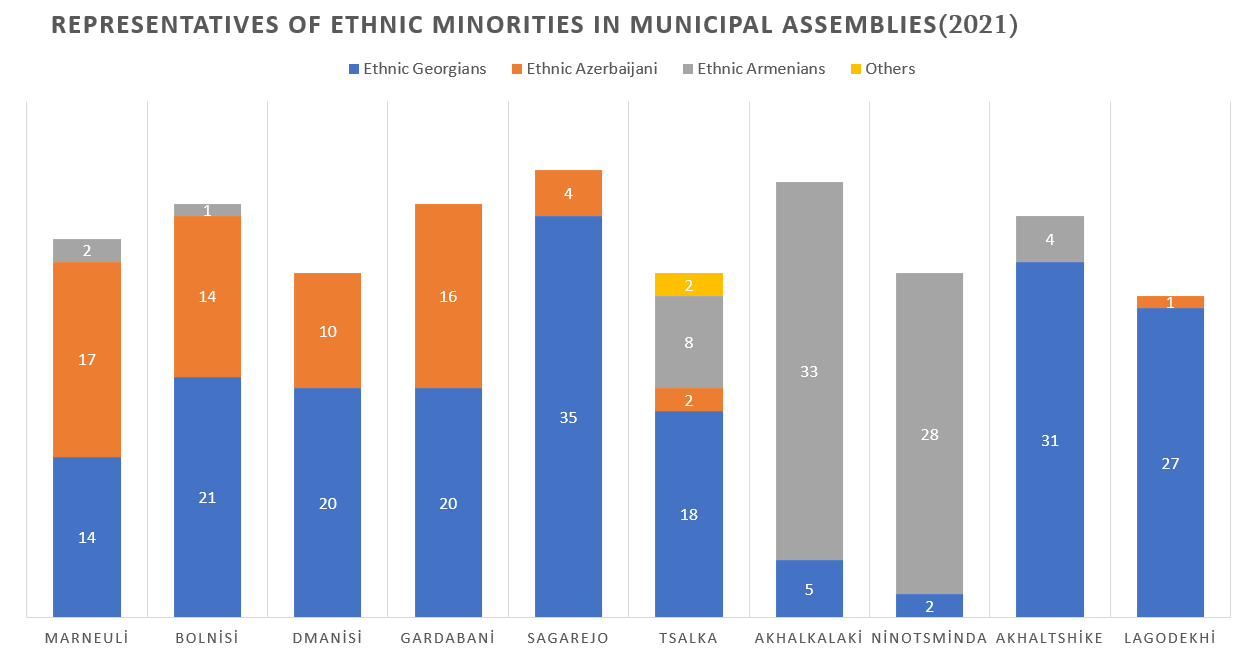

The representation of Azerbaijanis and Armenians at the local self-government level is also low. According to the results of the 2017 municipal body elections, in 8 municipalities densely populated by Azerbaijani and Armenian communities (Marneuli, Bolnisi, Dmanisi, Gardabani, Tsalka, Akhaltsikhe, Akhalkalaki, Ninotsminda), on average 779 ethnic Georgians have 1 representative in the Municipal Assembly, while 1,116 ethnic Armenians and 2,945 ethnic Azerbaijanis only had one representative each[11.]

Similar to 2017, the results of the 2021 municipal body elections show that the representation of the Azerbaijani community at the local self-government level is particularly low. Except for the municipalities of Akhalkalaki, Ninotsminda, and Gardabani, their representation in the assemblies of other municipalities densely populated by ethnic minorities is two to three times lower compared to their proportional share in the population, and in some cases even lower.

(The diagram was prepared based on the data available on the websites of municipalities)

(The diagram was prepared based on the data available on the websites of municipalities)

Except for Akhalkalaki and Ninotsminda [and partially Marneuli], in the rest of the municipalities, the representation of ethnic minorities in the commissions of the Municipal Assembly and various services and departments of the City Hall is, for the most part, quite small. In the municipality of Sagarejo, where the Azerbaijani community makes up 1/3 of the population, the highest position for them in the local self-government body is membership in the Municipal Assembly, and in Lagodekhi, where the share of ethnic Azerbaijanis is up to 25%, they have only 1 representative in the Municipal Assembly.

In conclusion, it can be said that creating an equal and fair environment for ethnic minorities in terms of political participation remains a problem, and the state policy does not address these challenges. It is necessary to develop and implement an action plan focused on specific and real goals in this direction. This may be in the form of improvement of the legal framework—financial incentives for political parties or other temporary mechanisms. Institutional barriers to the political participation of minorities need to be studied and evaluated in detail. It is also important to ensure the broad involvement of representatives of ethnic minorities in the process and take their opinions into account.

-

This material has been financed by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, Sida. Responsibility for the content rests entirely with the creator. Sida does not necessarily share the expressed views and interpretations.